This is an album I’ve been looking forward to writing about from the moment I created this blog. The product of Playboy Magazine’s first jazz poll, Hugh Hefner decided to create an album to honor the winners of the poll. By releasing such a project, Hefner and the folks at Playboy provided a snapshot of popular jazz circa 1956, in addition to accomplishing something rarely seen in the music industry- a truly cooperative effort that spanned record labels. Let’s jump to the music! Warning: This being Playboy and all, there’s a couple of pictures that may make you blush. Wink Wink. Also, grab some water and some food; there’s lots of music to discuss!

The Music

The Tune: “Play, Boy!”

Recorded: 15 July 1957 in Hollywood, CA

Personnel:

- Leader & Trumpet– Shorty Rogers

- Trumpets– Conte Candoli, Conrad Gozzo, Al Porcino, Pete Candoli, Harry Edison, Don Fagerquist

- Saxes– Park Adams, Richard Kamuca, Bill Holman, Jack Montrose, Herb Geller

- Trombones– George Roberts, Frank Rosolino, Bob Enevoldsen, Harry Betts

- Piano- Lou Levy

- Bass– Monty Budwig

- Drums– Stan Levey

The Tune: The Sophisticated Rabbit

Recorded: 25 July, 1957 in Los Angeles, CA

Personnel:

- Leader & Drums: Shelly Manne

- Trumpet- Stu Williamson

- Alto Sax- Charlie Mariano

- Piano- Russ Freeman

- Bass- Monty Budwig

The Tune: “A Playboy in Love”

Recorded: 31 July, 1957 in Los Angeles, CA

Personnel:

- Leader & Guitar- Barney Kessel

- Piano- Arnold Ross

- Bass- Red Mitchell

- Drums- Shelly Manne

The Tune: “Pilgrim’s Progress”

Recorded: 3 August, 1956 at Stratford, Ontario, Canada

Personnel:

- Leader & Piano- Dave Brubeck

- Alto Sax- Paul Desmond

- Bass- Norman Bates

- Drums- Joe Dodge

Quite simply, this is a cool album. It was revolutionary when it was released, a spectacular example of multiple record companies working together to create something new. In 1956, when Playboy Magazine was more glamour and less sleaze, Hugh Hefner decided to join the ranks of Down Beat and other jazz publications and start the Playboy Jazz Poll. During its heyday, it was (in Hefner’s own words) the most successful and popular jazz poll around. This may have been correct; I’m sure it was easy to fill out the poll when there were pretty girls on the opposite pages. Hefner didn’t mess around. According to the album’s copious liner notes, there were more than 20,000 ballots and over 430,000 individual votes. Pretty decent for a first poll. The window to cast a vote was pretty narrow, and the whole operation was rather official in nature. The first “page” of liners explains the rigorous process:

According to the album’s copious liner notes, there were more than 20,000 ballots and over 430,000 individual votes. Pretty decent for a first poll. The window to cast a vote was pretty narrow, and the whole operation was rather official in nature. The first “page” of liners explains the rigorous process:

“In accordance with the rules of the first annual PLAYBOY JAZZ POLL, only votes entered on the official jazz poll ballot in the October issue and postmarked before midnight, November 15th, were counted. In an unprecedented move to assure the authenticity of the poll’s results, all ballot envelopes were turned over, unopened, to Arthur Pos & Co., certified public accountants, who supervised the tabulating and verified the final count. Votes were entered on punch cards and tabulated by IBM. The final results follow, with the top 13 listed in each category.”

So there you have it. Side note: 1956 was the year IBM introduced their first computers to use hard-drive disks, holding a stupefying 5 megabytes of data (or 0.005 gigs). The computers took up a whole room, as this now quaint picture from ’56 shows.  From the results of this poll, Hugh Hefner and the folks at Playboy thought it would be a groovy idea to press a special album comprised of the winners of the poll, an ambitious project requiring the cooperation of numerous record labels. Against all odds, Playboy was able to do it. The two-record album is like a large compilation album (which, technically, I suppose it is), with music representing jazz from all over the place, from a Stan Kenton track from 1940 to music recorded a few months before the album was released in 1957. This album was also rather special in that much of the music included on here wasn’t released anywhere else. In fact, a few of the tracks were recorded especially for this project, making some of the tracks rare and hard to find. It’s these types of tracks that I decided to spotlight, as I was having trouble picking tunes to showcase for this feature.

From the results of this poll, Hugh Hefner and the folks at Playboy thought it would be a groovy idea to press a special album comprised of the winners of the poll, an ambitious project requiring the cooperation of numerous record labels. Against all odds, Playboy was able to do it. The two-record album is like a large compilation album (which, technically, I suppose it is), with music representing jazz from all over the place, from a Stan Kenton track from 1940 to music recorded a few months before the album was released in 1957. This album was also rather special in that much of the music included on here wasn’t released anywhere else. In fact, a few of the tracks were recorded especially for this project, making some of the tracks rare and hard to find. It’s these types of tracks that I decided to spotlight, as I was having trouble picking tunes to showcase for this feature.

Trumpeter Shorty Rogers wrote the tune “Play, Boy!” to celebrate being ranked (4th place) in the poll, and it’s a swinging number. Rogers occasionally led a big band, and this track features his big band, yet the music still breathes and swings like a small group. The arrangement is catchy and uses some wild, dense voicings, with the Candoli brothers screaming on the trumpets. The big band is made up of the West Coast’s best and brightest jazz men, with guys like Frank Rosolino, both Pete and Conte Candoli, Bill Holman, Herb Geller, and even Harry Edison, to name a few. I’m not sure who the saxophonist is who takes that initial solo, or the guy who takes the trombone solo (I suspect it’s Mr. Rosolino…), but I’m pretty sure Lou Levy takes the piano solo, and Herb Geller gets a brief couple of bars to make a statement as well. Shorty Rogers manages to sneak in and take a brief solo himself.

Drummer Shelly Manne took first place in the drum category, and thus decided to also write a special piece for the album. I like what the liner notes say about it (written by the great Leonard Feather):

“In “Sophisticated Rabbit”, written for and dedicated to the mascot of a certain men’s magazine that shall be nameless, Shelly offers a provocative minor motif in which his sidemen-trumpet, piano, tenor, bass-all have their turn at bat, with Shelly in the spotlight toward the middle of the performance.”

Shelly Manne was one of the more tasty, melodically-driven drummers jazz ever saw, and this track aptly makes that case.

In keeping with the obvious theme, Barney Kessel’s original tune “A Playboy in Love” is another example of a tune written especially for this project and thus appeared only on this album. The recording is less than five minutes, yet Kessel manages to fit an entire jazz suite into that time span. He introduces the theme in a slow, no-tempo opening, moving to more rhythmic variations, then turns the tempo up again for some good old jazz blowing. The melody is simple, yet effective; it’s like something you’d whistle while walking down the street (do people even whistle while walking down the street anymore?). To quote Mr. Feather once again, “It has form and continuity; composition and improvisation; a beautifully integrated rhythm team, and, above all, the mandatory intangible known as soul.” Needless to say, Mr. Feather designated this tune as the best thing on the album. High praise indeed.

Lastly, but certainly not least, we come to the longest track on the entire album, laid down by big winners of the Playboy Poll- the Dave Brubeck Quartet. Full disclosure: this was the main reason (ok, the only reason) I tracked down and bought this album. This live performance by the 1956 edition of the Dave Brubeck Quartet was originally only available on this album. The tune is an original of sorts, in that it’s a spontaneous exploration of the blues in B-flat minor. While Paul Desmond and the Brubeck brigade explored the minor blues initially in 1954 and numerous times after that, this version is slightly different in that they stay in the minor key the entire time instead of moving into the adjacent major key. The title, “Pilgrim’s Progress”, almost certainly came post-performance and was almost certainly Paul Desmond’s idea. Desmond and Brubeck’s minor blues performances were all shades of Desmond’s original tune “Audrey”, but on this occasion, it was sly named after another woman, namely Playboy’s favorite playmate at the time named Janet Pilgrim. Ms. Pilgrim was quite the looker in the mid-1950’s, as a Google search quickly showed. Or this 1956 photo that appeared in Playboy. And you thought the 1950’s was sweet and innocent.  It’s easy to see why this performance was named after her for its inclusion in this album, but with Desmond, there’s more than meets the eye. During Desmond’s solo on the track, he quotes Stravinsky’s “L’Histoire du Soldat”, or “History of a Soldier”. It’s not hard to see how Desmond’s mind could make the leap from “History of a Soldier” to ‘Christian soldier’ to ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ (a story about a guy named Christian soldiering on to the Celestial City) to Janet Pilgrim. That’s the mind of Paul Desmond for you.

It’s easy to see why this performance was named after her for its inclusion in this album, but with Desmond, there’s more than meets the eye. During Desmond’s solo on the track, he quotes Stravinsky’s “L’Histoire du Soldat”, or “History of a Soldier”. It’s not hard to see how Desmond’s mind could make the leap from “History of a Soldier” to ‘Christian soldier’ to ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ (a story about a guy named Christian soldiering on to the Celestial City) to Janet Pilgrim. That’s the mind of Paul Desmond for you.

Recorded live in 1956 at the Stafford Jazz Festival in Ontario, Canada, the tune features some haunting playing by Desmond and some climatic piano from Brubeck, with a short but tasty bass solo from Norman Bates (no joke. That’s his name). Drummer Joe Dodge provides kicks and interjections here and there to prod the musicians along. Writing the liner essay for Brubeck’s selection, Leonard Feather, who wrote an absolutely scathing review of Brubeck’s album ‘Time Out’ (which of course went on to become one of Brubeck’s most popular albums), reluctantly conceded that “No matter what the polemics in which we critics have indulged concerning the technical value of the contribution by this and that combo, there can be little doubt that with the help of Dave and Paul, their records and their in-person college tours, much has been accomplished toward the end of establishing jazz intellectually as music to listen to, to enjoy and study and dissect, rather than simply as an incitement to dancing or foot-stomping.”

The Dave Brubeck Quartet featuring Paul Desmond was riding high among jazz fans during the mid-50’s, as the Playboy Jazz Poll aptly illustrates. Individually, Brubeck and Desmond came out well on top in their instrument categories, with Brubeck surpassing Erroll Garner by almost 2,000 votes while Desmond carried a lofty 2,581-vote lead over Bud Shank. If that wasn’t ego-boosting enough, Dave Brubeck won the best instrumental combo category with a comfortable 2,000-plus vote lead over the Modern Jazz Quartet. Pretty good for a group that burst onto the scene a mere five years earlier in 1951.

The rest of the album features the other winners of the poll, with people as varied as Louis Armstrong (who was featured with a live song unavailable anywhere else for decades) and Charlie Ventura to more ‘modern’ guys like Bob Brookmeyer and Chet Baker. Stan Getz’s featured track is a cooking blues “Blues for Mary Jane”, which comes from his album ‘The Steamer’. The music overall is fantastic and noteworthy, particularly for the more rare tracks that for the longest could only be heard on this long out of print vinyl album. In the case of the Brubeck track, the album points to the fact that there’s tapes of live material languishing in a vault somewhere. As great as the music is, however, there’s some real visual treats in the album. To the album itself we go!

The Cover

I’m sure some readers will be confused as to how this apparently bland cover art garnered a ‘B-‘. For some reason, I truly like it. It’s clean, simple, yet modern in composition. The way the title is printed and displayed across the middle of the cover with various colors draws you in, while the names of the winners (in lower-case, because of hipness) descends vertically to give your eye somewhere else to go. In the middle is Playboy’s famous mascot, the rabbit with bow tie. This could have been made in 2018, and looks just as stylish now as it probably did back in 1957. Emmett McBain of Playboy Magazine, good on you. The cover was printed in that unique mid-50’s style of heavy gloss and laminate, which I happen to love. It feels durable, like it’ll last another fifty-plus years.

The Inside

There’s quite a few pictures here. You’ve been warned.

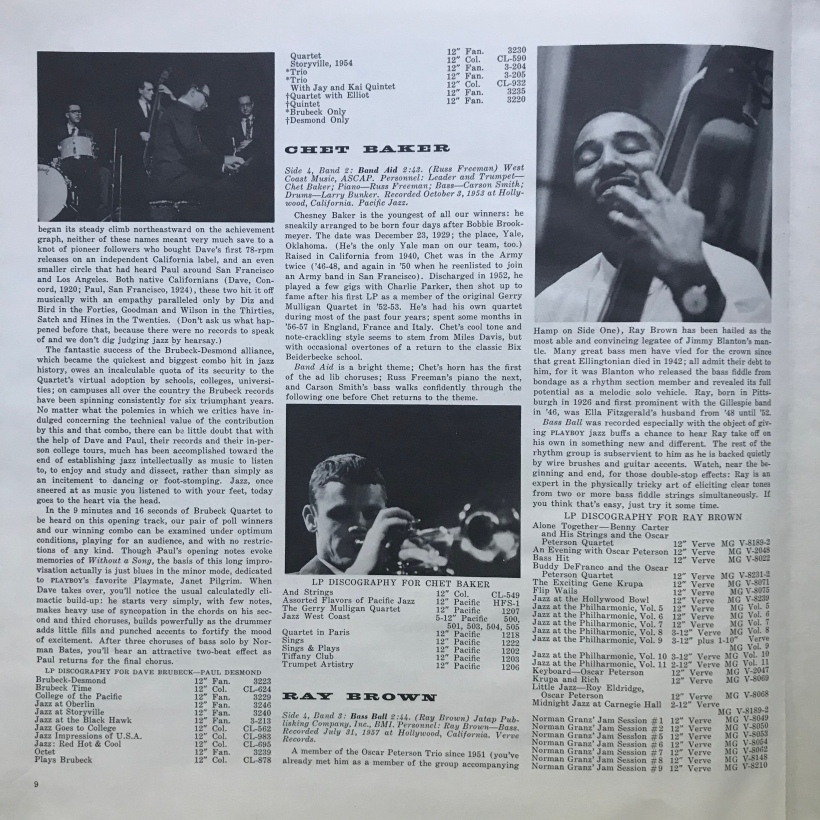

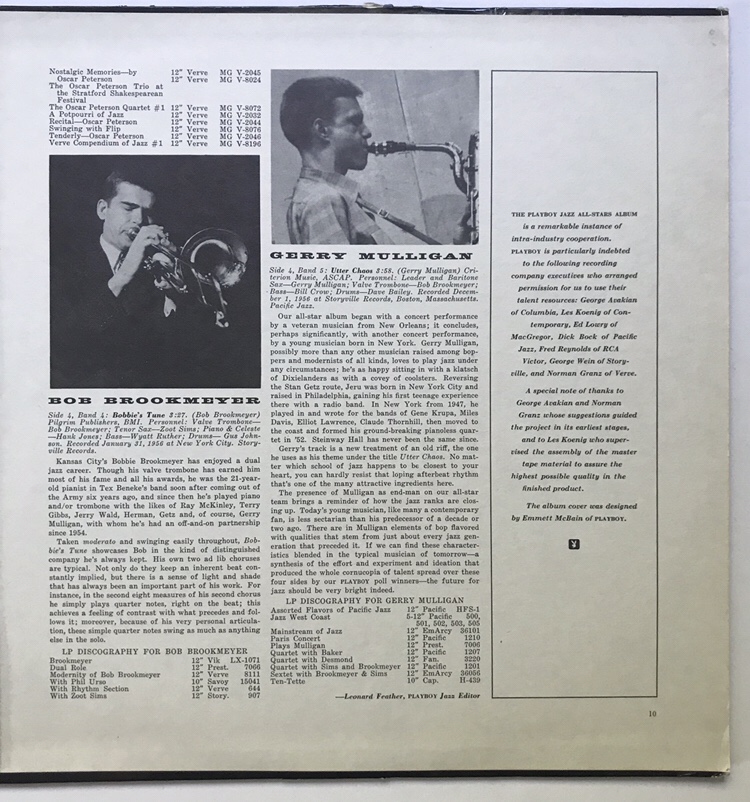

It’s not a gatefold album, and it’s not an album with inserts. It’s an album with a lengthy booklet directly attached to the inside. Ten pages, to be exact. It’s loaded with fantastic pictures, information, and even mini discographies for each artist. And of course, the all important results of Playboy’s first annual jazz poll. Written by the elder statesmen of jazz writing, Leonard Feather (who also happened to be Playboy’s Jazz Editor, which makes me wonder what he was writing about jazz in the magazine to result in these poll results), the liner essays are expertly written and full of analysis of the music and the artist.

It’s not a gatefold album, and it’s not an album with inserts. It’s an album with a lengthy booklet directly attached to the inside. Ten pages, to be exact. It’s loaded with fantastic pictures, information, and even mini discographies for each artist. And of course, the all important results of Playboy’s first annual jazz poll. Written by the elder statesmen of jazz writing, Leonard Feather (who also happened to be Playboy’s Jazz Editor, which makes me wonder what he was writing about jazz in the magazine to result in these poll results), the liner essays are expertly written and full of analysis of the music and the artist.

The results of the poll are immensely intriguing on many accounts, namely how it serves as a sort of snapshot of what jazz fan’s tastes were in the early years of jazz’s golden era. It’s a revealing look at the readership of Playboy Magazine in the mid-1950’s, as well. Looking at the names that made the rankings in each category and the names that actually took the top spots (and which names didn’t even make it at all), one gets the idea that Playboy’s main demographic tended towards one direction. They favored the newer West Coast jazz musicians, intriguingly enough, yet also liked the older jazz musicians from the early days of jazz like Jack Teagarden and Louis Armstrong.

What’s glaring is who’s NOT amongst the winners, or even ranked. For it to be 1956 and not have Clifford Brown (they included Art Tatum and Tommy Dorsey, who also died in 1956), Sonny Rollins, Art Pepper, or even Horace Silver make the top 13 is pretty incredible. And if that’s not enough, the people we record collectors and modern jazz fans would consider the greats are buried in the rankings. Miles Davis and Art Blakey are both in 8th place in their respective fields. Cannonball Adderley is 7th in alto sax, with Sonny Stitt right above him. Numerous conclusions can be drawn from this. I’d encourage you to go through the poll results when you have the time, as it truly is fascinating to see who Playboy readers of the 1950’s were listening to. Like Frank Sinatra, who I wouldn’t consider a jazz singer. Not a surprise that he was the favorite dude singer of 1956, but it’s a pleasant surprise to see Nat King Cole and Sammy Davis Jr. coming in second and third.

The Back

I really like this artwork. Other than the fact that it’s printed crooked on the album, this is a neat concept. This would make for a cool poster.

I really like this artwork. Other than the fact that it’s printed crooked on the album, this is a neat concept. This would make for a cool poster.

The Vinyl

Hugh Hefner was truly a visionary. From a small loan of $600, Hef built a magazine publishing brand and company, clubs, merchandise, and a tv show. Oh and a record label. The history of Playboy Records is a story of how humble beginnings can turn into a something much bigger. Started by Hefner in 1957 for this project, the label continued to grow, peaking in the 1970’s with a few huge hit singles.

In 1957, Playboy Records relied largely on the expertise of other record labels. George Avakian of Columbia Records and Norman Granz of Verve played a particularly special role in the making of this album, and Contemporary Record’s Les Koenig handled the tape and record pressing and supervision. In fact, upon looking at the all-important runnout info in the vinyl, it reveals that Koenig had the album pressed by Contemporary Records. Side one has “P B-1957-12-1- D1”. I’m not sure what the 12 means, but I’m pretty sure the other part is the label and catalog number, followed by side 1. According to London Jazz Collector, the D1 signifies a first pressing. An ‘H’ in the runnout indicates it was pressed by the RCA Hollywood pressing plant. The other codes in the runnout have ‘D1’ or ‘D2’. The vinyl is deep-groove, with first edition Playboy labels. I like how they made it so that the eye of the rabbit is the actual record hole (is there a more official term for the middle of the record?). One annoying thing about this album and old double-record albums is how they number the sides. Why is side 4 on the back of side 1?! Why is side 3 on the back of side 2?! It makes absolutely no sense at all, and nobody has been able to adequately explain the logic of this practice. Why wouldn’t you put the records in consequential order? Can somebody explain that to me?

The sound on this album is fantastic, particularly the tunes recorded in the studio especially for this project, leading me to think Lester Koenig had a bigger role in the album’s production. Even the live track with Brubeck was recorded excellently, given the circumstances. Of course, this is all in glorious mono, recorded on the eve of that shiny new toy called stereo’s life.

The Place of Acquisition

eBay. Nothing too special, other than this was among the first albums I bought on eBay way back in 2015. Playboy released two more projects like this one, with the production and packaging acquiring more bells and whistles with each release, with their final release in 1960 being the grandest. I will own them all sooner or later, as they’re all highly collectible. According to reviews and Hugh Hefner, these albums were pretty popular. Of course, Hefner was able to utilize product placement and milk it for all it was worth…

Speaking about the third and final Playboy set, Hefner said that “A three-record set produced by Playboy based on the first Festival was a smash hit that has since become a treasured collector’s item.” Luckily they’re not too hard to find, as they rate pretty low on the totem pole with most record collectors, particularly the record collectors with money. Which, naturally, is fine with record collectors with no money, like myself.

Hi.

First of all congratulate him on his blog whose publication I follow and read carefully for months. Thank you very much for your work.

Regarding the numbering of the faces of the double lps, it makes sense if one thinks that at the time of publication, reproduction equipment with an automatic disc change system was common, so if you put the face 1 and then the face 2, by going around the group of two discs directly orders the 3 and 4 cras. I think I read somewhere that this is the reason for such a peculiar numbering.

I hope I’ve been useful.

Greetings from Toledo, Spain.

I’ve read your comment 50 times, googled the topic, and it still doesn’t make sense to me! Thank you for your explanation, though.

Sorry. I meant faces 3 and 4, naturally.

Scandalous! I love this post and I learned so much! Thank you!

Automatic changer sequence! Take side 2, place it over side 1 and plop it on the changer. When the two sides have finished, flip the stack over and put it back on the changer. Sides 3 and 4 play in sequence. You’ve never seen this before? Very common from the 40s through the 70s.

Ah! That makes a ton of sense, and I never thought about that before. I’ve seen it on a few double-LP albums that I have but never knew the logic, especially since some didn’t follow the same numeric sequence. Thanks for the explanation.